- Home

- Mick 'Baz' Rathbone

The Smell of Football Page 7

The Smell of Football Read online

Page 7

I was just 20 then, Bails was 22. He informed me he would take me for a slurp with ‘The Birch’ – Alan Birchenall. We went to Angels nightclub in Burnley. I was really drunk after only three pints of lager – I hadn’t really drunk that much since the incident in Holland three years previously. When I got back to my room I vomited into my suitcase, all over my clothes for the next day. I went to training for the very first time with my new club with a terrible hangover.

How ironic that I had somehow contrived to make the same mistake again – to turn up for an important ‘first impressions’ training session with a raging hangover. Who said lightning doesn’t strike in the same place twice? It does with prats like me.

I walked into the dressing room and Birch introduced me: “This is Mick Rathbone, but we will call him Basil (after ’30s actor Basil Rathbone).” That was in March 1979, and the name stuck. I am now known by everybody as Baz – my wife and mom call me Michael, but to everybody else I am Baz.

To my surprise and total delight, I was greeted by everybody at the club and in the town itself with something approaching reverence – a whole new sensation for me. Being from a First Division club and an England youth international obviously counted for something up here. My God, I can’t begin to tell you how good that felt after what I had been through. The lads and the staff were great. They were genuinely friendly, full of banter and mickey-taking as you would expect, but this time it was done good-naturedly and with affection and respect, which was a whole new ball game.

I tasted the ‘Lancashire Life’ – cobbled streets, gravy on chips, steak puddings and flat caps. What a great place. I still live there now and I consider myself a true Blackburn lad 30 years on. The people of Blackburn were and are the salt of the earth, so friendly and genuine. All of a sudden, everybody wanted to know me. I was instantly respected. I was almost a star player. There were no Villa fans to give me stick because I played for the Blues or, more importantly, no Blues fans to give me stick because I played for the Blues.

It all felt so very different. I felt wanted, important, but most of all I felt respected. My self-esteem was starting to return and – whisper it – I was really looking forward to playing. Yes, me. It had been such a long time since I had experienced that feeling.

Why did I feel so much better up here? Well, nobody knew me, nobody expected too much from me, so I felt the slate had been wiped clean and it was a fresh start. When I went into town, nobody shouted, “Wanker.” In fact they came over and asked for my autograph or asked the classic question all fans ask and to which there is no answer: “Are we gonna win Saturday, Baz?” At night I walked up to the West View public house (without Bails), and people came over, sat, talked, bought me a pint and spoke to me with genuine affection. I felt so much at home. This was it. This was how it should have been at Birmingham – to be fair, if I had played a bit better it probably would have been.

Rovers were actually doomed to relegation that season, bottom of the old Second Division and needing snookers to survive. When I got there we had 16 games to go. I made my Rovers debut in March 1979 at the Racecourse Ground against Wrexham. We lost 2-1 but that didn’t matter one iota because, for the first time in ages, I enjoyed the match. I played well. I actually wanted the ball to come to me. I didn’t want the game to end. My legs weren’t filled with lead. I had tons of speed and energy. I was shouting for the ball. I had lots of confidence – it had been so long that I’d played with any self-belief.

It just all seemed so easy, so effortless. Was it easier? Was the standard inferior? Well, up to a point, it had to be. I was playing in a lower division, but I prefer to think my improved performance was more down to the fact I had regained voluntary control of my fucking lower limbs. Was it a different style of play? It was for me, because now I wasn’t bombarding the people in Row Z with my passes.

After the game I remember being very emotional – a mixture of joy, relief and almost bitterness at the terrible experiences of the last few years. But this was different now, this was how it was meant to be. I could do it. I could be a player.

The rest of that season was nothing short of brilliant. Although relegation was unavoidable, John Pickering rallied us and we had some great results – away at Stoke and Sunderland in particular, who were at the time first and second in the league. I was starting to get a good reputation. People were saying good things about me now on the radio, in the newspapers and on the phone-ins. People were saying I was a very talented player again and that felt so good – not out of vanity, but sheer relief that my career had not been completely destroyed at Birmingham.

I loved the players – John Bailey, Alan Birchenall, John Waddington, Noel Brotherston, Derek Fazackerley, Paul Round, Glen Keeley, Simon Garner and Joe Craig. Or as I knew them – Bails, Birch, Waddy, Noel, Faz, Roundy, Keels, Garns and Craigy.

The most important thing was that we were equals. Now, instead of lying awake all night terrified of hearing the crunch of the paperboy’s feet on the gravel, I would race up to the local newsagents to read all the good things people were writing about me. It was footballing paradise, and the pride I would feel over the next eight years every time I pulled on that fantastic blue-and-white-halved shirt never diminished.

However, through all this rediscovery of me as a player, one thing had completely slipped my mind. I was technically only on loan and, therefore, still a Birmingham player and, horror of horrors, they insisted I returned to them at the end of the season. It was a real body blow when John Pickering told me Jim Smith had been on the phone and wouldn’t let me move to Blackburn permanently. I was totally shattered. One thing was for sure, though – I couldn’t and wouldn’t go back. Back to the fear, the frustration of being crap through no other reason than nerves, back to being criticised, undervalued, back to the reserves. I decided extreme situations call for extreme measures, so I plucked up my courage and phoned the Bald Eagle.

Not to put too fine a point on it, I begged him to let me stay. I pleaded with him. I told him I could never do it at Birmingham. Again, he showed a side of him that few people knew. Understanding and compassionate, he relented – although the stingy sod insisted on a fee of £40,000 which was a fortune for a provincial club to pay for a 20-year-old, especially a provincial club that had just been relegated. But with the generous help of the club chairman, David Brown (co-founder of the Graham & Brown wallpaper company), the deal was done and I signed a three-year contract at Rovers on £120 per week.

As I had been away from Birmingham on loan for three months prior to my permanent signing, there was no real impact or reaction to my departure – except a huge sigh of relief from the fans! I did pop back one day to say goodbye and collect my spare boots, but all the players were off and my boots had disappeared. A fitting end, I suppose.

In those days, players received five per cent of any transfer fee, so I took my £2,000 and bought an Alfasud motor car. Things were finally looking up. Young, well-off (relatively), posh car (for the ’70s), and much more importantly, respected as a footballer, I went away for the summer break truly happy and at peace with myself – I had confronted and overcome all the demons that had threatened to shatter me. I felt I had been right to the edge of the precipice and stepped back at the last minute. I had no illusions I could ever be anything other than a decent reliable player – some of the damage done at Birmingham was permanent – but compared to the shell of a player I had become there, I was only too happy to settle for that.

That initial loan period and subsequent signing started an eight-year spell of great personal and professional happiness. I established a wonderful rapport with the Blackburn supporters, married a fantastic local girl and became part of this fine town. I was flattered and somewhat choked a couple of years ago when I ran on to Ewood Park to tend to a player and there was some sporadic applause and a few cries of “Go on Baz” from some of the Rovers fans – presumably the older ones.

But it would take time for me to earn that respect fr

om the fans. It wasn’t all plain sailing after I completed my transfer and, within a few months, I faced a completely new and unexpected set of problems.

That close season – the summer of 1979 – had been class. I think I was entitled to feel proud of myself, a commodity that had been in short supply for several years. Troy romped home in the Derby, Maggie romped home in the general election and the Alfasud quickly turned into a blue Ford Capri and then, in quick succession, a very fast Triumph Dolomite Sprint, my dream car – teal blue, OBN 894R, black roof with a sunroof, overdrive. Three cars in three months – a perfect way to get rid of any surplus cash.

The ’70s were nearing an end now – lapels were coming in, ties getting thinner, trousers tapered at the bottoms, shoes with pointy toes, mullets and New Wave music was on the radio. I was so looking forward to going back to the chimneys, cobbled streets, gravy on chips and famous blue-and-white halves of Blackburn Rovers. It was with great excitement and anticipation that I packed my cases, slid them into the boot of the ‘Dolly’ and set off back to Blackburn – or home as I was already calling it.

What was it like to be young, free, single, somewhat famous (OK only in Blackburn), and reasonably well-off? I had a newfound confidence and new-found self-esteem. Mercifully, I had once again become the same outgoing, fun-loving guy I had been at school and in my first year at Birmingham City. Regrettably, though, I was about to fall into the same trap that even now, more than 30 years on, young players are still falling into.

You can’t put an old head on young shoulders, they say, and within a few weeks I would be failing again as a footballer. However, this time it was not through lack of confidence or self-belief, but lack of maturity and discipline.

I had stayed in the Woodlands Hotel while on loan the previous season, but now I had to find some digs to live in. We had signed Russell Coughlin from Manchester City. He was 19 years old, from Swansea, a great little lad and a good player. He was stocky and compact (that’s being kind) but immensely skilful, and we became good pals.

We decided we would share digs on our return to Blackburn, so in July 1979 little Russ and I moved into Trevor Close in Blackburn to share a bedroom in the house owned by the delightful Harry and Hilda Wilkinson – great people, sadly both now passed away. So there were me and little Russ – young, free and single, with disposable income, both discovering beer, nightclubs and girls at the same time.

You can probably guess what happened next. I think most nutritionists and sports scientists would agree that boozing seven days a week, regularly staying up until the early hours of the morning and living on crisps, steak puddings, chips and beer is likely to have a detrimental effect on one’s physical condition, and slowly but surely, Russ and I drank and ate ourselves out of the game.

Looking back, it was a bloody disgrace the way we conducted ourselves and let down the club that had put so much faith in us, but it seemed fine at the time and when you are young, immature and stupid the penny doesn’t really drop until you are a good way down that road to nowhere.

Even when I was in such poor physical condition that I had to walk in the pre-season cross countries – despite the fact I had been a champion 800-metre and cross country runner at school – it still didn’t really register that I was on the verge of stealing defeat from the jaws of victory.

Why? Why did I act like such a total idiot to the point that, for the sake of a good night out, I would jeopardise this second chance? I suppose it was the thrill of being away from home, that little bit of ego creeping in now I was one of the ‘star players’, and certainly an element of not realising the damage I was doing to my body and career.

This is how Russ and I lived: we would get back from training at lunchtime and go straight out for a couple of pints, often down to the Orchard Working Men’s Club where it was about five pence a pint. Then we would have a couple of games of pool and five or six pints of cheap beer before returning to the digs for a wash and change at which point our drinking could start in earnest.

We always started proceedings at the Farthings pub just by our digs. We developed a bizarre little ritual in that he would go straight to the bar while I went straight to the jukebox to put on I will Survive (ironic or what?). He would then bring the drinks over and I would say, “Bloody hell, Russ, why did you get four pints?”

“Well, you know the boss said to rest and save your legs for the weekend – that’s what I am doing, saving my legs,” he would reply in his strong South Wales accent.

We always used to laugh, even though we repeated the same jokes every night. Then we set off on our pub crawl, but always ended up back at the Farthings just on the stroke of last orders where we had another couple of pints each, courtesy of Russ’s ingenious energy-saving strategy.

Next, it was time for the highlight of the whole evening. We used to walk to a chippy and Spar shop just up the road. Bearing in mind little Russ had a slight weight problem – no, sorry, a big weight problem – to the extent that our new manager, Howard Kendall, was repeatedly telling him to go on a diet or face the consequences, what happened next was quite incredible.

Russ would go into the Spar and buy an uncut loaf of bread before heading into the chip shop to buy what he affectionately referred to as the “full mog” (that classic delicacy of the region – steak pudding, chips, peas and gravy in a tray). He would then, with an admirable degree of manual dexterity belying the fact he had just had 12 pints of Daniel Thwaites’s finest, proceed to hollow out the middle of the uncut loaf before tipping the full mog into the middle of it.

Finally, just before consuming what must have been in the region of 5,000 calories’ worth of food, Russ would issue these profound words: “Baz, phone Howard will you and tell him the diet starts tomorrow.” We would then laugh hysterically at this well-used and rehearsed joke.

Yes, we had become complete pillocks. But my God, we were having a great time, courtesy of the Danile Thwaites brewery and Hollands Pies. The trouble was it was having a seriously damaging effect on my football.

I was, sadly, back on familiar ground – playing crap. The only difference this time was that it was totally self-induced. The reason my legs weren’t functioning now was not down to lack of confidence, but the fact I was out on the piss every night of the week.

Incredibly, I made the starting line-up for the first game of the season at home to Millwall. It was a baking hot day and, not to put too fine a point on it, I was fucking knackered. I was playing like a zombie and had already been responsible for giving away their goal.

I got sent off just after half time for arguing with the referee – difficult to do in those days, but somehow I managed it (maybe he could smell my breath). As I walked along the touchline in disgrace, somebody shouted, “Get him on a health farm, Kendall!” It was a small town and people knew what was going on.

After the game, Howard was going mad at me, saying I had let everybody down and was a fucking disgrace to the shirt. Which, looking back, of course, I was. He banned me for three months but, to be fair, I wasn’t even bothered. I was on the slippery slope to Dyno Rod again and it would take something special – miraculous even – to get me out of this nosedive.

But guess what? A few days later, that much-needed miracle happened.

I was in the Beechwood Pub (surprise, surprise), enjoying my new-found freedom with Russ, who was doing nearly as well as me. He had scoffed and boozed his way on to the transfer list. Then I saw this gorgeous girl playing on the fruit machine. I staggered over and apparently made some crude remark about my plums or her melons – you can just imagine it, can’t you? I actually half-knew her – she was the sister of John Bailey’s girlfriend – and I asked her out on a date.

The rest is history. It was one of those instant attractions where I knew immediately this was the person who I wanted to spend the rest of my life with. Luckily, she felt the same (or so she said – maybe she just wanted to marry a famous footballer, in which case it turned out to be a bad night f

or her).

We knew then we were destined to be together. We were married within the year and have now been married for nearly 30 years. She saved my life, my career, my self-esteem. Without Julie, there would be no book because there would be no story. They say behind every great man there is a great woman. If I can reverse that theory, I must be an incredible guy.

Julie’s parents allowed me to move into their spare room. I had some stability in my private life at last. No more boozing or late nights – just think football. Slowly but surely, and with their help, I rehabilitated myself. I hauled myself back from the brink, started playing well in the reserves, got back into the first team and enjoyed an unbroken seven-year period, when fit, as first-choice full back for Blackburn Rovers. I got my physical fitness back and transformed myself from the clown who had to walk in the cross countries to the guy who won them by a huge margin – all due to that chance meeting. I shudder to think what would have happened to me if Julie had stayed in to wash her hair that night.

I learned a lot from that brief but very traumatic period: how everybody, with a given set of circumstances, has the capacity to self-destruct. It’s still happening today. Young players – rich, famous, away from home – history repeating itself. So when I read lurid tales of footballers in the Sunday papers, getting pissed and misbehaving, I think back to my ‘off-the-rails’ days and understand it’s a simple trap to get into, but a bloody difficult one to get out of.

Oh, and if you are interested in what happened to little Russ . . . when I left the digs to move in with Julie and her family, he was upset because we had become as close as brothers. Not wanting to stay on in the digs on his own for the remainder of the season he moved into some fresh and novel accommodation – his car. Amazingly, he went to live in his little green Chrysler Sunbeam, which he parked in the car park next to Ewood Park. I can still see him now coming into training every day for a shower and a cuppa, toothbrush in mouth, wearing his slippers while whistling the tune to Travelling Light.

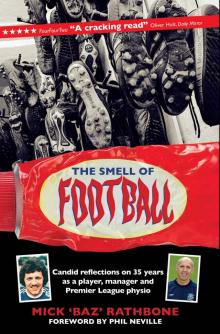

The Smell of Football

The Smell of Football